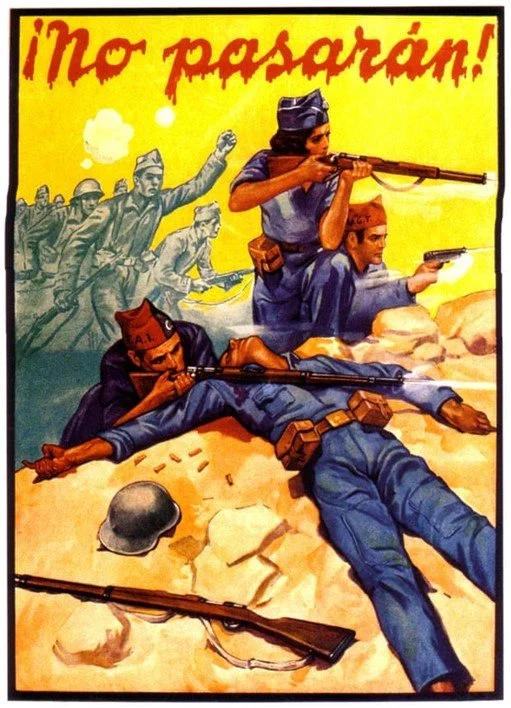

Spanish Civil War - – No Pasaran

“The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.” Marx, The Communist Manifesto

The Cides believe that the Spanish Civil War (1936 –1939) was a result of the people waking up to the centuries where religious propaganda had been used to control them. The newly formed republic fought against a coup from Franco back by the ruling elite - the church and monarchy, that kept them impoverished and barely surviving.

Since early 2020 world leaders have blatantly used propaganda to create fear of a virus and its variants. Many of us have recognised that the narrative is to bring a planned agenda to fruition by creating a ‘window of opportunity’ to lead us down the fascist path to a totalitarian one-world governance.

Unfortunately, there are others, who through continuous consumption of that media propaganda, fail to see what we are being subjected to, and by accepting the narrative as the truth and acquiescing, they are aiding and abetting an agenda that only benefits a tiny percentage of people. An agenda that has been and will be ever increasingly detrimental to themselves and the rest of humanity.

This has been the experience of the Spanish people for centuries, however, the propaganda that they were subjected to came from the trinity of the monarchy, the Catholic Church and the army that kept the people impoverished in a totalitarian governance through the fear of going to hell. The Spanish Civil War between 1936 – 1939 was a genuine revolution from below.

The Origins of Conflict

The Spanish Civil War is often said to be the first battle between democracy and fascism and a prelude to the second world war, however, it was more than this. Conflicts existed with regionalists against centralists, anti-clericals against Catholics, landless labourers against latifundistas (large estate owners) and workers against industrialists.

The social structure that created these strains was shaped as far back as the Reconquista in Spain which effectively drove Muslims out of the Iberian Peninsula. The warring against the Moors went on intermittently for centuries, beginning in the eighth century and ending in 1492. The long crusade formed the attitudes of the Castilian conquerors and in the 15th century the triumphal entry into Granada and dynastic marriage of Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon (the ‘Catholic Monarchs’) saw the beginning of Spain’s civilisation.

The Spanish Empire became one of the first global powers as Isabella and Ferdinand funded Christopher Columbus's voyage across the Atlantic Ocean. A route was established enabling the Spanish conquest of much of the Americas, this helped accumulate enormous wealth for the Spanish elite consisting of a trinity of monarchy, church and army accumulated enormous wealth through the colonisation and domination of South America giving them a “superiority” over the rest of Europe.

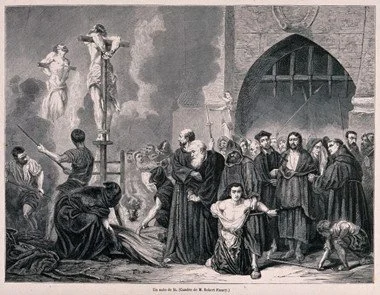

The Totalitarian Catholic Church

Continuous glorification of Ferdinand and Isabella the Catholic monarchs had begun and together with a feudal army, they formed the prototype of state power. The Church was utilised as a propagandist for military action which they also participated in and remained closely connected to the army during the rapid growth of Spain’s empire. The Army conquered and the Church integrated new territories into the Castilian state. Together they exerted power over the population, assisted by the threat of hell and hell on earth in the form of the infamous torturous Inquisition in the Holy Office which was to weed out ‘heretics’.

Essentially the Catholic Church and Monarchy created the totalitarian state by controlling every aspect of education, including the burning of books, in order to extinguish political and religious heresy and using spiritual justification for their actions. According to British military historian, Antony Beevor, this “placed the entire population in a protective custody of the mind,” and few countries have been more closely identified with Catholicism than Spain.

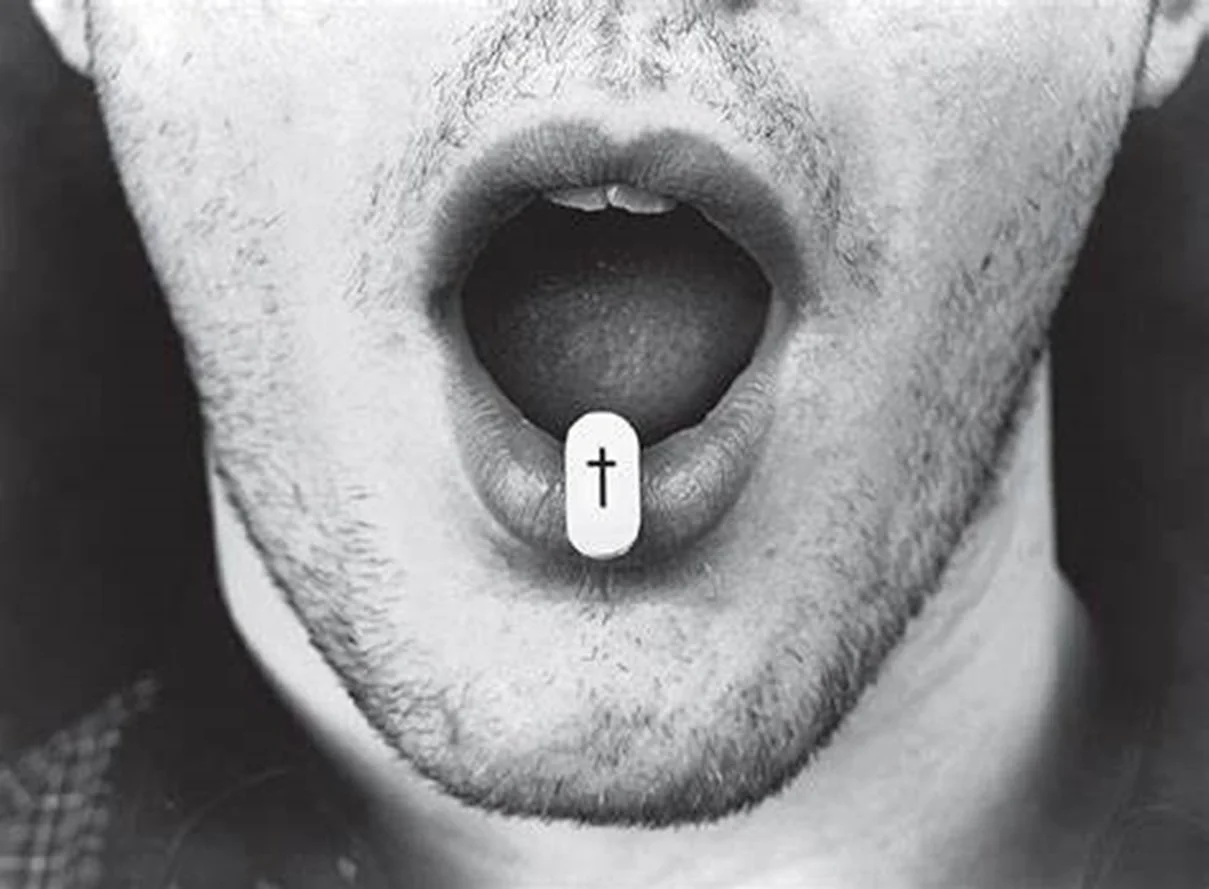

Religion - The Opium of the Masses

It could be argued that this is due to being driven by guilt which according to Charles Darwin in his work the Origin of the Species those individuals tended to survive. The Catholic Church certainly evoked a sense of guilt while also creating the fear of punishment from a divine entity. ‘Big Gods’ were ready to mete out punishment encouraging prosocial behaviour. This theory aligns with the medieval belief of the Divine Right of Kings, the political and religious doctrine that claims monarchs were given their ruling role directly from God, therefore legitimising and defending monarchical absolutism.

Karl Marx believed by promising eternal life in heaven for those who adhere to the beliefs also made it less likely that the proletariat would challenge the social order, as it would also be directly challenging God. According to Marx, religion was used to distort reality and numbed the pain of the oppression experienced by the proletariat and therefore religion was the ‘opium of the masses.’ This would have benefited the proletariat through their endurance of suffering, which the Spanish monarchy praised as Castilian qualities (source).

Trance Hypothesis

An interdisciplinary team of academics may have proved Marx right after finding that the origin of religion possibly stems from the Palaeolithic period. They realised that synchronised activity in groups released endorphins, the neurotransmitters stored in the pituitary gland which are known to promote pleasure, relieve stress and alleviate pain, and group activity saw tension eased, and prosocial behaviour amplified. Ecstatic experiences could be induced which the team, led by Oxford professor of evolutionary psychology Robin Dunbar, terms the “trance hypothesis.”

Although our ancestors started dancing, drumming, imbibing, chanting, feasting and fasting, this was a step on from experiencing awe and wonder and meant altered states of consciousness could be explored. This was supported by another psychologist, Miguel Farias, who studied the effects of endorphins in religious settings. Farias found that endorphins rise even with modest levels of collective behaviour such as standing to sing hymns and kneeling to pray (source). This may explain why the people of Spain were able to be so easily governed by the Church.

This may also explain why the clergy still represented a centralised force in Spain alongside the monarchy, and in union with it. The Clergy possessed “great wealth” and “still greater influence” according to Leon Trotsky who said that the state spent “many tens of millions of pesetas” annually for the support of the clergy which consisted of close to 70,000 monks and nuns during the 18th century. This equalled the number of high school students and doubled the number of college students.

Trotsky asked “Is it a wonder that under these conditions forty-five per cent of the population can neither read nor write? It is no wonder at all especially when it was the Church and the landlord class who worked together to keep peasants impoverished and rigged the ballot box and judicial system denying them justice?” (source).

The Feudal Agricultural Society

Yet in 19th century Spain, which was still evolving from a feudal agricultural society, nobles were scorned if they worked productively, it was the Spanish peasants who were expected to not only pay taxes but also perform the backbreaking agricultural work on the land, feeding the country while they themselves lived in destitution and sometimes starvation.

Peasants worked on the surrounding latifundios as jornaleros (casual labourers, hired by the day or for specific tasks) which meant enduring the humiliating slave market ritual of arriving at the plaza (village square) each day at dawn in the hope of being called by the landowner. which served to reinforce the hierarchical structure of local society. They lived in earthen floored huts using branches and straw as covers. They often struggled to survive and illness, disease, and babies being abandoned or even killed were often the result of extreme poverty, and crime was common as desperate people resorted to desperate measures.

The “Inglorious and slow, decay”

Clearly, the industrial and liberal revolution had succeeded in transforming other European countries but had barely touched Spain. The hegemony that they once had over Europe coincided with dominance of world trade, but in the nineteenth century, the exploitative Spanish colonial system was not as concerned with trade as other European countries. Yet the South American Colonies that had enriched the nation were lost to them in 1820 and finally Cuba in 1898, meaning Spain was clinging on to a past where they had superiority, but now without those same resources.

The condition which Marx called “inglorious and slow, decay” settled down upon feudal-bourgeois Spain, a result of the slowness of capitalist development and the withering of economic relations which acted as a “brake on the formation of the nation” according to Pierre Broué (1961). Spain’s backwardness weakened centralist tendencies inherent in capitalist systems and with the decline in commercial and industrial life along with economic ties and lack of economic development, mutual dependence within individual provinces lessened due to a decline in commercial and industrial life and economic ties.

Broué adds that the classes in the old regime continued to disintegrate, without completing the formation of the emergent bourgeois society. The economic stagnation also decomposed the old ruling classes and “the proud nobleman often cloaked their haughtiness in rags”. All because, as Leon Trotsky said “the old and new ruling classes – the landed nobility, the Catholic clergy with its monarchy, the bourgeois classes with their intelligentsia – stubbornly attempted to preserve the old pretensions”.

Reform and Reaction

The feelings of indisposition in all parts of the country could only foster separatist tendencies and as a consequence, Spain was split into two antagonistic social blocks, although continual attempts had been made to introduce reforms focusing on land and a redistribution of wealth, they were blocked by reactionary efforts from the few who were attempting to retain their privileged positions.

Spanish history was already dominated by the revolutionary outbursts in the 1850s, 1870s, 1917 and 1923 due to the reactionary efforts of the political and military power attempting to hold back progress (source).

In 1930, Primo de Rivera was forced to resign. King Alfonso XIII called for democratic elections, ushering in the First Republic and five years of social unrest, during which the political right and left vied for control. Elections held in April 1931 went overwhelmingly to the republican parties, forcing King Alfonso XIII to abdicate and flee to England. The government of the Second Republic led by Manuel Azaña was composed of a coalition of the middle-class republican parties and the right wing of the Spanish Socialist Party, the Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE).

The PSOE provided a left-wing cover for a strictly bourgeois government and acted in the interests of the old ruling elite, failing to challenge the financial and industrial capitalism that had merged with big landowners one of the biggest was the Catholic Church, leaving the many who hoped for a better life disappointed at the inaction and led to them taking measures into their own hands, including the widespread burning of churches.

Old Habits

Even passively, monarchism still had overwhelming support in Spain and remained a force and political danger through their reluctance to accept the Republic. However, the position of the Catholic Church had progressively weakened and their methods to keep their hold over Spain were revealed to be through their control of state schools which allowed free play of anti-liberal doctrines. but, when a republican government based on a Liberal Socialist alliance came into office in April 1931, they had three main tasks to resolve, the land, the army and to remove education from the Church. Not one of these tasks was resolved (source).

Instead, they acted in the interests of the old ruling elite and failed to challenge the financial and industrial capitalism that had merged with big landowners of which one of the biggest was the Catholic Church, leaving the many who hoped for a better life disappointed at the inaction. In 1934 the government was replaced by a reactionary dictatorship and was met with an enormous uprising of opposition by the working class and poor peasantry.

The Republic

In February 1936, the Republicans came to power with support from Anarchists and POUM (the workers’ party of Marxist Unification formed in 1935 by a fusion between former supporters of Trotsky (Nin, Andrade) and Catalan nationalist ex-CP members). Manuel Azaña formed a coalition between parties of the middle-class and main workers’ parties, (the Socialist Party (PSOE), Communist Party (PCE), Esquerra Party and the Republican Union Party). The coalition became known as the Popular Front.

On the other side were the Nationalists, the rebel part of the army, the bourgeoisie, the landlords, and, generally, the upper classes, strengthened by the support of fascist Germany and Italy, which meant they were better armed. Unlike the popular front, however, they were now armed with the experience of 1931-33, this time the left wing of Partido Socialista Obrero Español – the Spanish Socialist Workers Party (PSOE) prevented the right wing from joining the government.

Other lessons had been learnt too, the workers and poor peasants did not wait for the new government to act but took immediate action and liberated around 30,000 political prisoners, and between February and July there were 113 general strikes, 228 other major strikes and peasants began to occupy the land.

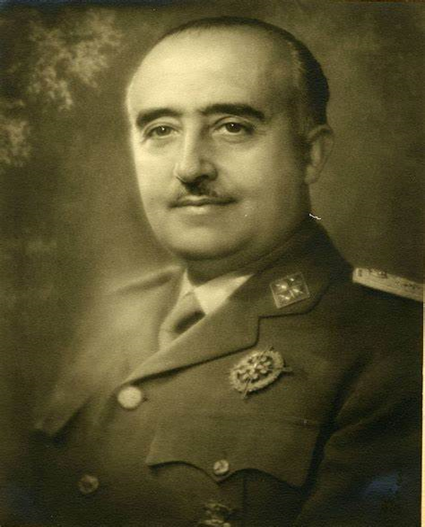

The Fascist Coup

As far as the ruling class was concerned the Popular Front victory was a declaration of war resulting in many abandoning their half-hearted support for the Republic and supporting the fascists instead. High-ranking army officers, monarchists, and fascists began plotting a military coup and army garrisons revolted in most major cities under the direction of the dictator General Francisco Franco. A coup was launched by Spanish military leaders on 19th July 1936, leading to an all-out civil war, an attack not only on the Popular Front government but also on those that voted them into power - the working-class organisations. They were threatened with a proclamation from the military leader, General Gonzalo Queipo de Llano declaring that the leaders of any labour union on strike would “immediately be shot” as well as “an equal number of members selected discretionally.” (source).

Although the Popular Front government had known of the uprising within hours, they remained silent and only provided a note the next day stating they were confirming “the absolute tranquillity of the whole Peninsula”. In an attempt to avoid confrontation and appease the fascists, they then dissolved their government which was reformed to include right-wing politicians. The working class were left to lead the struggle against the fascists alone (source).

The Republic Became Defenders of Privilege

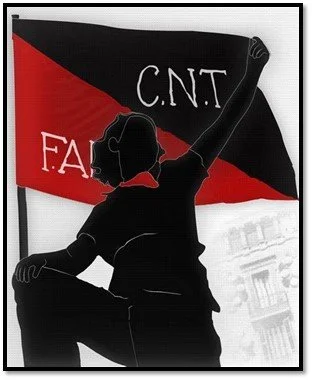

The appeasement of the ruling elite continued and when the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo – the anarcho-syndicalist National Confederation of Labour (CNT) and the Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT) (the general union of workers) – the second biggest trade union federation, led by the Socialist Party, demanded that the Popular Front government arm the workers, they refused. The government argued that only by restraining the demands of the workers and peasants could it maintain unity between all antifascist forces, including the bourgeoisie.

Consequently, with the support of the PSOE and the communist party (PCE), the government:

Passed restrictions on the ability of peasants to seize large land holdings

Restricted workers’ ability to run factories under workers’ control.

Passed laws stating that the private property of foreign firms would be seized under no condition.

Together with civil governors, refused to cooperate with the working-class organisations that were needing arms.

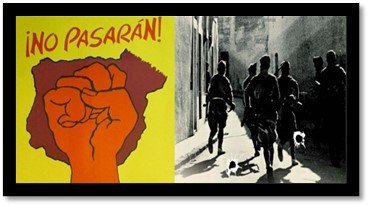

No Pasaran!

In many cases, this brought the success of the risings and signed the civil governors' death warrants, along with local working-class leaders (source).

Steadfast in their convictions the working class bravely continued to take action and when the Republican Army chief propagandist and member of the Communist Party (PCE) Dolores Ibarruri declared in a speech at a meeting for women: "It is better to be the widows of heroes than the wives of cowards!". On 18th July 1936, she ended a radio speech with the words: "The fascists shall not pass! No Pasaran". This phrase became their battle cry.

While bravely holding back the fascists, the workers parties:

Stormed army barracks seized weapons and distributed them to anyone with a trade union or party membership card.

Quickly organized defences,

Creating armed patrols,

Arrested fascist sympathisers

Built barricades

Formed anti-fascist village committees

Expropriated land, harvests, cattle, tools etc, from landlords’ reactionaries.

Notably, the hatred for the Church that had aided a totalitarian regime was evident in the first six weeks of war as almost 2,894 priests, nuns and bishops were killed from the church hierarchy, including thirteen bishops (source).

Within days, the revolt was defeated in many cities and the anti-fascist militia successfully pushed back the fascists and “held power in their hands”.

Anarchists in Spain

Spanish anarchism emerged as a combination of peasants, petty-bourgeois individualism, direct action against the state and trade unionism. However, together the groups shared the basic principles of anarchism – opposition to elections and parliamentary activity and also to all forms of hierarchy.

Initially, Spanish anarchism had a strong following that was greater than socialism aided by the creation of the CNT the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (confederation of labour) the anarcho-syndicalist National Confederation of unions in Barcelona. Although the CNT had existed on the factory level since 1918 it was suppressed under the Primo de Rivera dictatorship, but re-emerged as a major left-wing movement in Spain in 1931 and was committed to the transformation of society.

The movement became not only the driving force behind a social revolution but an active participant in an increasingly modern conflict which would eventually see thousands of its affiliates such as the FAI (Federación Anarquista Ibérica which has also been referred to as the CNT-FAI) and militants serving on the frontline within the Republican army (source).

Anarchists were strongest in Barcelona and had installed their headquarters in the former premises of the Employers’ Federation and had used the Ritz as ‘Gastronomic Unit No 1’ a public canteen for all those in need. They also took over all the services, the oil monopoly, the shipping companies, heavy engineering firms, Ford Motor company, chemical companies, the textile industry and more. (source)

The CNT in fact was in control of much of Republican Spain and in the capital Barcelona, the leaders of the CNT-FAI were told by the head of the regional government “Today you are masters of the city and of Catalonia.... You have conquered and everything is in your power.”

It could be argued that due to a lack of support from a Republican government this was not to be and eventually after a bloody but heroic battle the Worker’s army was defeated by Franco and the Fascists (source).

The European Fear of “Hitlerism”

The Spanish Civil War presaged the opening of the floodgates for the horrific new and modern form of warfare that was dreaded universally with a collective fear of what the defeat of the Spanish Republic might mean. Benito Mussolini and his Fascisti had taken power in Italy in 1922, followed by Hitler’s Nazis in Germany in 1933.

There were those from the left in 1936 that could see what the democratic right failed to see for another three years, that Spain was the last bulwark before “Hitlerism.”

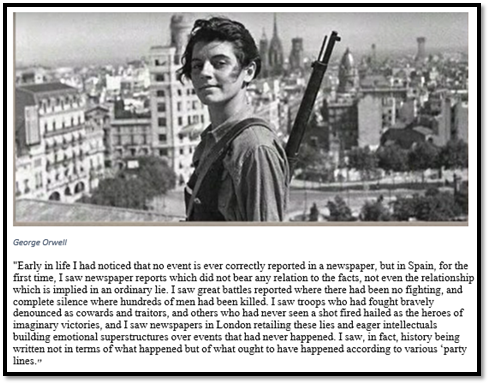

As a result, approximately 40,000 people from 53 different countries arrived in Spain to join the brigades fighting the war against Franco. These international volunteers knew that by fighting fascism in Spain they were fighting for their democratic rights and freedoms in their own countries too. More than 2,300 came from British and Irish factories and mines as well as writers such as Ernest Hemingway, Upton Sinclair and George Orwell who joined the POUM (Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification).

1936 and 1984 and 2020

George Orwell said “every line of serious work I have ever written since 1936 has been written directly or indirectly against totalitarianism”. His novel ‘Nineteen Eighty-Four’, is defined as a “dystopian social science fiction novel” and a “cautionary tale”, however, it is arguably more the latter. Although we have seen quotes from the book and Orwell himself increasing over the last few years on social media, have we been sufficiently warned by them?

The 1936 Spanish Civil War (and George Orwell novels) should raise awareness. The methods used then have been the methods used again today and in other years when world leaders have committed atrocities in their quest for total governmental control – the lies, the propaganda, the indoctrination, the incitement of fear, the division of the people, all in order to usher in a fascist regime.

We all need to wake up to this fact fast and make “No Pasaran” our own battle cry and not let them pass!

Research by Patricia Harrity